Introduction to the Karnak Temple Complex

The Karnak Temple Complex, commonly known as Karnak, is a vast collection of temples, pylons, chapels, and other structures near Luxor, Egypt. This remarkable site, with its roots tracing back to the reign of Pharaoh Senusret I (1971–1926 BCE) in the Middle Kingdom, showcases the grandeur of ancient Egyptian architecture. The construction spanned over millennia, continuing into the Ptolemaic Kingdom (305–30 BCE), with most of the existing structures dating from the New Kingdom period.

Karnak, known as Ipet-isut in ancient times, meaning “The Most Selected of Places,” was the primary worship site for the Theban Triad, with the god Amun at its head. The complex is part of the ancient city of Thebes, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1979. The name Karnak derives from the nearby modern village of El-Karnak, located 2.5 kilometers north of Luxor.

Karnak is an open-air museum and one of the most visited historical sites in Egypt, second only to the Giza pyramid complex. Its vast expanse includes four main parts, although only the Precinct of Amun-Re is open to the public. The other sections—the Precinct of Mut, the Precinct of Montu, and the dismantled Temple of Amenhotep IV—are not accessible to visitors. Numerous smaller temples and sanctuaries connect these precincts, forming a rich tapestry of ancient religious architecture.

The Precinct of Amun-Re: The Heart of Karnak

The Precinct of Amun-Re is the largest and most significant part of Karnak, dedicated to Amun-Re, the chief deity of the Theban Triad. This section features colossal statues, including the 10.5-meter-tall figure of Pinedjem I, and one of the largest obelisks, standing at 29 meters tall and weighing 328 tons. The sandstone for these structures was transported from Gebel Silsila, 100 miles south on the Nile River, illustrating the impressive logistical capabilities of the ancient Egyptians.

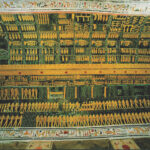

A key highlight of the Precinct of Amun-Re is the Great Hypostyle Hall. Covering an area of 50,000 square feet, it boasts 134 massive columns arranged in 16 rows. The central columns are 21 meters tall with a diameter of over 3 meters, and the architraves on top of these columns are estimated to weigh around 70 tons. Theories about how these massive stones were lifted include the use of levers or large ramps made of sand, mud, brick, or stone.

The Precinct of Amun-Re showcases the architectural prowess and religious devotion of ancient Egypt. Its structures, built over centuries, reflect the evolving religious practices and political power of Thebes, the capital of unified Egypt during the Eighteenth Dynasty.

The Precinct of Mut: Ancient and Unrestored

The Precinct of Mut, located south of the newer Amen-Re complex, is dedicated to Mut, the mother goddess. This section is one of the oldest parts of Karnak and has several smaller temples associated with it, along with its own crescent-shaped sacred lake. The temple of Mut has suffered significant damage, with many portions reused in other structures. However, recent excavations have unearthed over 600 black granite statues, highlighting its historical significance.

Restoration efforts by the Johns Hopkins University team, led by Betsy Bryan, have allowed the Precinct of Mut to be opened to the public. Discoveries in this precinct include evidence of festivals involving overindulgence in alcohol, reflecting the complex religious practices and cultural celebrations of ancient Thebes. The intertwining of deities like Sekhmet and Bast into Mut’s identity over time illustrates the dynamic nature of ancient Egyptian religion.

The Precinct of Mut provides a glimpse into the religious life of ancient Thebes, from the worship of the mother goddess to the festivals and rituals that were central to the culture. Its ongoing restoration continues to reveal new insights into the ancient world.

The Precinct of Montu: Dedicated to the War-God

The Precinct of Montu is dedicated to Montu, the war-god and son of Mut and Amun-Re. This smaller section, located north of the Amun-Re complex, reflects the martial aspects of ancient Egyptian religion. Although it is not open to the public, the Precinct of Montu adds another layer to the rich religious landscape of Karnak.

Montu was a falcon-headed god associated with the sun and war. His precinct, though less visited, holds significant historical value. The presence of various temples and structures dedicated to Montu indicates the importance of war and military prowess in ancient Egyptian society. The god Montu was often invoked for protection and victory in battles, underscoring the connection between religion and state affairs.

While the Precinct of Montu remains closed to visitors, its historical and religious significance is undeniable. It highlights the diverse pantheon of gods worshipped at Karnak and the multifaceted nature of ancient Egyptian spirituality.

The Temple of Amenhotep IV: A Dismantled Legacy

The Temple of Amenhotep IV, also known as Akhenaten, was constructed outside the walls of the Amun-Re precinct. Akhenaten’s reign is noted for the brief introduction of Atenism, a monotheistic worship of the sun disk Aten. Following Akhenaten’s death, his temple was dismantled as the powerful priesthood of Amun sought to erase his revolutionary changes.

This temple’s remnants offer a fascinating glimpse into one of the most controversial periods in ancient Egyptian history. Akhenaten’s attempt to shift religious practices away from the traditional gods to a single deity was met with resistance and eventually undone. The dismantling of his temple reflects the strong opposition to his reforms and the restoration of the traditional religious order.

The story of the Temple of Amenhotep IV underscores the political and religious turbulence of the time. It serves as a reminder of the complex interplay between religion and power in ancient Egypt, where pharaohs could rise and fall based on their religious policies.

The Architectural Evolution of Karnak

Karnak’s architectural development spans several centuries, with contributions from approximately thirty pharaohs. This long history of construction and renovation has resulted in a complex that is both vast and diverse, reflecting the changing religious and political landscape of ancient Egypt. From the Middle Kingdom to the Ptolemaic period, Karnak evolved into a site of unparalleled architectural and cultural significance.

The sheer scale of Karnak is a testament to the dedication and resources invested by successive rulers. Each pharaoh added their mark, from monumental structures and towering obelisks to intricate carvings and statues. The contributions of rulers like Thutmose I, Hatshepsut, and Ramesses II have left an indelible legacy, making Karnak a living document of ancient Egyptian history.

The diversity of deities represented at Karnak, from early gods to those worshipped later, showcases the site’s religious significance. Karnak was not only a place of worship but also a center of cultural and political power, reflecting the grandeur and complexity of ancient Egyptian civilization.

Hypostyle Hall: An Architectural Marvel

The Great Hypostyle Hall in the Precinct of Amun-Re is one of Karnak’s most iconic features. Covering an area of 50,000 square feet, it contains 134 massive columns arranged in 16 rows. These columns, with their open papyrus umbel capitals, create a breathtaking forest of stone, demonstrating the architectural ingenuity of the ancient Egyptians.

The construction techniques used to build the Hypostyle Hall are still debated by scholars. Some believe that levers were used to lift the heavy architraves, while others propose the use of large ramps made of sand, mud, brick, or stone. Regardless of the method, the construction of such a massive structure required immense skill and precision.

The Hypostyle Hall is not only an architectural feat but also a testament to the religious devotion of the ancient Egyptians. The hall was designed to impress and inspire, with its grand columns and intricate carvings depicting various deities and pharaohs. It remains one of the most awe-inspiring sights at Karnak, drawing visitors from around the world.

The Historical Context of Karnak

The history of Karnak is closely intertwined with that of Thebes, the ancient city in which it is located. Thebes became the capital of unified Egypt during the Eighteenth Dynasty, leading to significant construction activities at Karnak. Early constructions, such as the small column from the Eleventh Dynasty mentioning Amun-Re, provide glimpses into the site’s ancient past.

Major construction efforts during the Eighteenth Dynasty included the erection of monumental structures by rulers like Thutmose I and Hatshepsut. Hatshepsut’s twin obelisks, one of which still stands, are a testament to the grandeur of her architectural projects. The Red Chapel, intended as a barque shrine, and the Great Hypostyle Hall, likely begun during this period, highlight the extensive construction activities at Karnak.

The later additions by pharaohs such as Seti I, Ramesses II, and Merneptah continued to shape the complex, with structures like the First Pylon and the Avenue of Sphinxes marking significant developments in the site’s layout. The history of Karnak is a testament to the enduring legacy of ancient Egyptian civilization.

The Decline and Rediscovery of Karnak

Following the Roman emperor Constantine’s recognition of Christianity in 323 AD, many pagan temples, including those at Karnak, were abandoned. Christian churches were established among the ruins, with the most famous example being the reuse of Thutmose III’s Festival Hall as a Christian church. This transition reflects the broader cultural and religious shifts in the region.

European knowledge of Karnak remained limited until the 15th and 16th centuries when explorers and scholars began documenting their travels to Egypt. Early accounts and drawings, though often inaccurate, paved the way for a better understanding of the site. The detailed descriptions by scientists during Napoleon’s expedition in 1798-1799 provided valuable insights into Karnak’s architecture and history.

The rediscovery and preservation of Karnak have been aided by modern technology. In 2009, UCLA launched a website featuring virtual reality digital reconstructions of the Karnak complex, allowing people worldwide to explore its architectural wonders. These efforts help to preserve and share the rich history of Karnak with a global audience.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Karnak

Karnak Temple stands as a testament to the architectural genius and religious devotion of ancient Egypt. Its vast complex, built over centuries by numerous pharaohs, reflects the grandeur and complexity of Egyptian civilization. From the Precinct of Amun-Re and the Great Hypostyle Hall to the Precincts of Mut and Montu, each part of Karnak tells a story of power, faith, and ingenuity.

The ongoing preservation efforts ensure that Karnak’s legacy continues to inspire and educate future generations. As we explore the history and architecture of this magnificent site, we gain a deeper appreciation for the achievements of ancient Egyptian culture.

[…] the most striking features of Luxor Temple is the avenue of sphinxes that once connected it to the Karnak Temple, another monumental complex in Thebes. This processional route, lined with hundreds of sphinx […]

[…] the most striking features of Luxor Temple is the avenue of sphinxes that once connected it to the Karnak Temple, another monumental complex in Thebes. This processional route, lined with hundreds of sphinx […]